Last night, I was on-air with Wolf Blitzer discussing the election, and I started to say something along the lines of “well, Wolf, we know this election will be close.” I paused and immediately corrected myself. When the data show the race as a toss-up - as they very much do - it is easy to slip into characterizing uncertainty about who will win as certainty that the race will be close.

I am not certain of who will win, and I am not certain that the race is close.

If you’ve come looking for a prediction, you’ve come to the wrong place. The closest you’ll get is this chat I did with

and Frank Bruni over at The New York Times. Instead, I want to dig into why there is such an appetite for prediction around this election, and why everything feels so especially on-edge.There are three reasons you might want to know the upcoming election’s result ahead of time. The first is if you are in the financial sector, seeking to make trades based on the result, where having foreknowledge of the likely outcome will give you an edge. The second is if you are working on a campaign and you want to know how best to change the future to be more favorable for your candidate.

But if you are not working on a campaign or looking to make trades on the election result in some way, then you are in the third bucket: you want to know because you are curious, or worried, or simply cannot live with uncertainty.1 Maybe you’re like a kid shaking the Christmas presents under the tree, trying to find out if the box contains a Playstation or a lump of coal, except the box is the Pennsylvania electorate and which candidate is the lump of coal will vary.

We no longer live in a world where this stuff is of interest mostly to a few political junkies on the primordial internet. We now have betting markets and at-home-use Magic Walls and a multitude of forecasting models. I’ve been trying to think through why it is the case that, at the same time that people seem more and more agitated with and distrustful of polling, hunger for the electoral predictions they supposedly fuel seems only to have grown.

A few weeks ago, a friend who follows elections and politics professionally asked me what I thought this election was all about. In past years, it has been clear what question voters are being asked: are you better off than you were four years ago? Who will be best at keeping America safe?

These days, when we ask voters what their top issues are, the economy usually comes to the top of the list, followed by an assortment of topics from abortion to immigration as a strong second-tier.

But that’s not the same question as what is this election about, to you? I test-drove this concept in my latest focus group for The New York Times and wasn’t disappointed. Look at the words these voters used when I kicked off the group and simply asked them what the election was about: “power”, “truth”, “democracy”, “values”, “freedoms”, “change”.

We asked this in our most recent Echelon Insights survey as well. Only 16 percent specifically mentioned something about the economy being a driving factor. Only 7 percent specifically mentioned abortion or women’s rights. Of course, I’m sure many of the people who said something more general about “getting back on track” or “protecting my rights and freedoms" meant the economy and abortion as part of their answers, but I am struck by how this election can’t be boiled it down to one issue. Mark it down, some pundits are going to try their hardest: if Harris wins, it’ll be “it was abortion that did it!” and if Trump wins, it’ll be “it was the economy that did it!” but I’m here to tell you that voters this year are generally talking about this election up one level higher from the specific individual issues themselves.

A reasonably representative selection of open-ended responses:

“Getting this country back to a place all citizens can be proud of.”

“This is going to be a turning point on whether our democracy lives on or dies.”

“My right to exist, live, and be free.”

You may think you know which party someone is voting for from those answers. I assure you, you do not. For all that we are so divided, I am struck by the way in which many Trump and Harris voters alike are talking about the election in these terms.

To flesh it out a bit more, it goes something like this. Trump and Harris voters alike seem to both agree with the following premise:

Our country is badly off-track. Too many of our leaders try to divide rather than unite. Our economy isn’t working for everyone. Our laws punish some people while letting others off the hook. Our institutions have proven they can’t be trusted to do what is right. Our democracy seems completely dysfunctional and like the voice of the people is being silenced. Our right to live healthy lives in peace and and safety are under threat. We need a leader who will be strong enough to stop the madness.

If you’re a Harris supporter, you view Trump as the cause of most of the madness: it is his Supreme Court that overturned Roe and sowed uncertainty for women, it is his rhetoric and demonization of people of color or transgender people that has driven us to hatred, it is his economic policies that will enrich only his buddies, it is his anti-democratic instincts that will silence dissent, it is his flagrant disregard for the law that has exposed how the wealthy and powerful can get away with anything these days.

If you’re a Trump supporter, you think perhaps only Trump can stop the madness: imperfect as he may be, only he can jump-start a broken economy, only he can hold back the state expanding its reach and silencing those who break from elite consensus, only he can protect people who wish to live by their faith or see important values upheld, only he only he can stop the weakness that allows criminals to break our laws with impunity, only he can stop a world on fire from continuing to burn.

For a long time, the question of “is the country on the right track or the wrong track” had been a useful political barometer. When people say we are on the “wrong track”, that usually spells bad news for the incumbent party. If you take a look at Gallup’s tracker of people’s general dissatisfaction with things in America, in decades gone by it tracked nicely with whether or not people voted out the party in power.

Ever since the summer of 2020, satisfaction with “the way things are going in the U.S.” has basically been in the toilet. You don’t get to numbers that bad without people from both parties feeling unsatisfied with the status quo. This is why both Trump and Harris have tried to paint the other as the de facto incumbent, the one responsible for the way things are now.

That’s also why it is more complicated than saying this is a “change” election. Everyone wants change! Everyone feels like we cannot keep going on like this, like something has to give, like our nation is losing its collective mind.

They are simply very, very divided over how to stop the madness: whether only banishing Donald Trump from public life for good OR putting Donald Trump back in charge can hold back the rising tide of insanity.

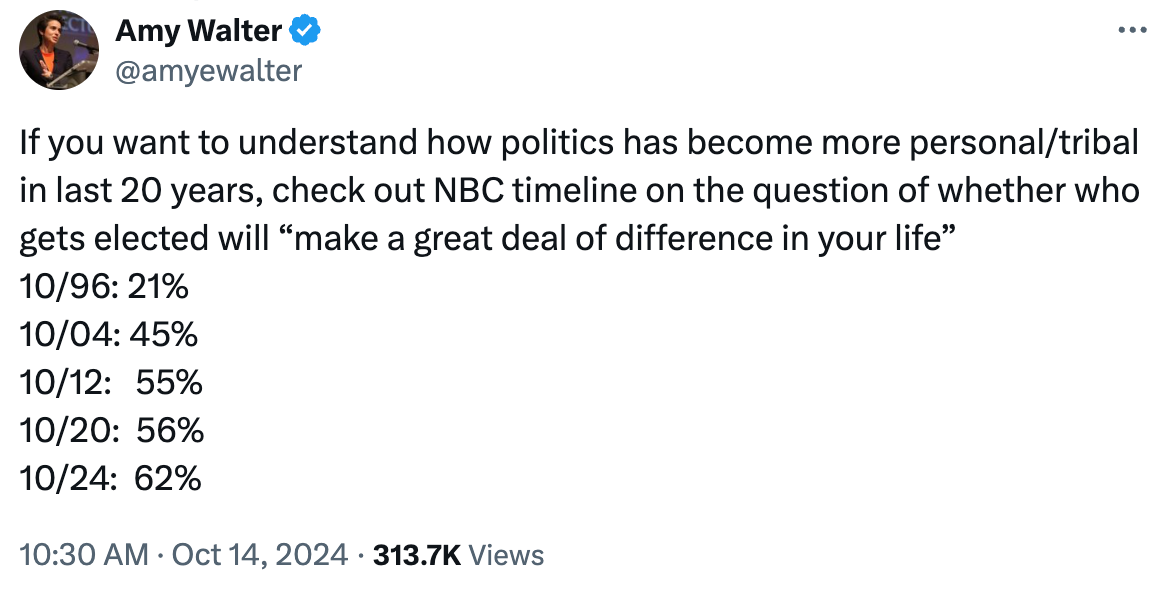

Every election of my lifetime has supposedly been the most important election of my lifetime, but this time around, voters do seem to mean it. Take this trendline, unearthed by Amy Walter, finding Americans increasingly likely to say that whoever gets elected will make a great deal of difference in their lives:

After the 2020 election, I went on Ezra Klein’s podcast to discuss the mood of the Republican Party post-January 6th. Ezra was alarmed by a poll finding put out by my firm, which showed that when you asked voters whether the goal of politics was to enact public policy or to ensure the survival of the nation as we know it, Republicans were much more likely to choose “survival”.

I wanted to see if this finding still held, if it was still Republicans who held a uniquely apocalyptic view of our politics. We asked it again, and found that not only were Republicans even more convinced that the goal of politics is “ensuring the survival of the country as we know it”, but Democrats had almost caught up to them.

We also tried out a different way of asking the question specifically focused on the 2024 election, seeing if people view the election as a contest of policy ideas in which the country will ultimately be OK, or an existential decision in which the national will be irreparably harmed if the wrong candidate wins.

As you can see, four out of five voters think this is an “existential decision”. It cuts across all kinds of lines. Men think so. Women think so. Seniors think so. Gen Z thinks so.2 The consensus is that this is bigger than simple disputes over public policy. This is why this isn’t really just an election about the price of milk. It’s not about whether you’re getting a Playstation under the Christmas tree. It’s not just “the economy, stupid” this time.

This is why people have begun treating election forecasting like coastal residents watching the path of a hurricane, waiting nervously for the next update to the “the cone of uncertainty”. When you think things in the country are a dumpster fire and that the election could either stop the madness or enflame it, and that your life, personally will be a great deal different under one regime or the other, you want to prepare accordingly.

I’m sorry that I can’t do that. I’m sorry that the best I can say is to prepare for a wide range of possible outcomes, because the “cone of uncertainty” on this one is wide. There are polls asking you to believe that Kamala Harris is winning men over the age of 65 in Iowa . There are about a thousand polls saying the race is 49-49, on a knife’s edge. There are data points suggesting Trump-supporting Republicans might, yet again, be especially disinclined to respond to polls, or that older white Democrats are in an especially poll-taking kind of mood lately.

As Nate Cohn puts it, when analyzing the notoriously strong Times/Siena polls:

Across these final polls, white Democrats were 16 percent likelier to respond than white Republicans. That’s a larger disparity than our earlier polls this year, and it’s not much better than our final polls in 2020 — even with the pandemic over. It raises the possibility that the polls could underestimate Mr. Trump yet again.

We do a lot to account for this, but in the end there are no guarantees.

I have grown to really dislike the way polls are treated entirely as a predictive tool, as if a poll that shows a result that is a few points off in the end is somehow useless. Even a well-executed poll is not going to be a great way to pin down within a point or two how an election might go. There’s margin of error, to say nothing of the countless issues that an inject bias into a result. The ballot test is often the least useful or important thing we ask in a poll. The vast, vast, vast majority of opinion research conducted in America today is not conducted to predict, but to explain: to give marketers or communicators or social scientists information about why things are happening, not to say what will happen with a high degree of precision.3

So what I have for you is not a prediction, merely an explanation. When you ask me what I’m hearing, and you are looking for some nugget of crosstab insight or early vote data that unlocks the secret of who will win, that’s not what I’m hearing.

I am hearing that Americans think we have to stop the madness.

I certainly hope we do.

“What do you hear, Starbuck?”

“Nothing but the rain.”

If you are so inclined, I’ll be on CNN on Election Night working the after-hours shift from 2 am until 9 am. We will have plenty of results to sift through. Put on a pot of coffee and join us. Otherwise, see you on the other side.

I know there are a lot of you out there, because you’ve all been texting me asking “what’s your gut say?” and so forth and I’ve not been responding. Very sorry.

Funny enough, it is elder millennials and young Gen X-ers who are the most likely in our poll to say the think America will probably be OK in the end.

The exceptions to this are extremely large sample, well-funded government surveys, but that’s a post for another day.